Clinical Information

Cataract Extraction

What is Cataract?

A cataract is an opacity or cloudiness that develops in the lens of the eye, which normally does the focusing. This will limit the amount of light that enters the eye causing a gradual reduction in vision. If left untreated, the cloudiness will continue to progress causing blindness. However, the blindness is reversible following treatment with an operation, unlike glaucoma where the blindness is permanent.

Cataracts normally develop with age but babies can also be born with them (congenital cataracts). Cataracts can also be caused by injury to the eye or certain medications, such as steroids.

Symptoms of Cataracts

Cataracts usually advance very slowly and patients usually notice a gradual blurring of vision. Cataracts do not cause any eye pain. The other symptoms that may be noticed are glare, increasing myopia (short-sightedness), double vision, impaired colour or depth perception and nyctalopia (impaired night vision).

The Treatment of Cataract

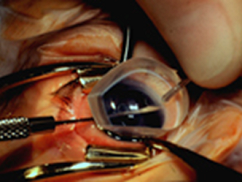

There are no drops or medications that will cure cataracts. In the early stages, new glasses can improve vision. However, once the cataract progresses the only effective treatment is surgery. Cataract surgery is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedure in the UK and is usually a very safe operation. The operation is performed through a small incision in the eye. Phacoemulsification (ultrasound technology) is used to remove the cataract and an artificial lens is implanted at the end of the procedure to allow normal vision (the implant). The benefits of phacoemulsification are a rapid healing time, minimal post-operative astigmatism, no need for sutures, few post-operative visits. Good vision can usually be achieved without the need for glasses for everyday wear but reading glasses will still be required. The operation is usually carried out under local anaesthetic but is completely painless. Most patients are treated on a day case basis, which means they do not need to stay in hospital overnight.

Glaucoma?

What is Gluacoma?

Glaucoma is a group of diseases in which there is progressive damage to the optic nerve (the nerve which transmits light signals from the eye to the brain). The main risk factor for this damage is elevated eye pressure (intraocular pressure), although not all glaucoma is caused by raised pressure. Initially, the disease does not cause any symptoms but if progressive, there is a loss of the peripheral visual field and eventually can lead to blindness if not treated.

What causes pressure within the eye?

Fluid (aqueous humour) is produced inside the eye by a layer of cells known as the ciliary body. The fluid is necessary for the normal functioning of the eye. The fluid drains out of the eye through a structure called the trabecular meshwork. The normal pressure within the eye is between 12 and 21mmHg. If there is an obstruction to the flow of fluid out through the trabecular meshwork, the pressure can rise and glaucoma can develop.

Types of Glaucoma

There are many different types of glaucoma but the two main types are closed angle and open angle glaucoma.

Open angle Glaucoma

Open angle glaucoma is the most frequent type of glaucoma and affects over 2% of adults over the age of 40 years. It becomes more common with increasing age, myopia (short-sightedness) and possibly diabetes. It also is more common and can be more severe in certain ethnic groups, especially blacks. The exact cause of glaucoma is unknown but it does tend to run in families and it is therefore important that relatives are checked by their optometrist on a yearly basis. Open angle glaucoma is a slow insidious disease which usually affects both eyes. Progressive damage to the optic nerve causes loss of peripheral vision and eventually blindness. The visual loss is gradual and completely painless.

Closed angle Glaucoma

Closed angle glaucoma is less common in the UK. It is more common in elderly patients and those of Oriental race. It is also more frequent in hypermetropes (long-sighted).

Closed angle glaucoma can present very suddenly when the eye becomes very red and painful. This occurs because the trabecular meshwork becomes blocked and the eye pressure rises dramatically. This sudden onset can be preceded by intermittent symptoms such as seeing haloes or rainbows around lights. This type of glaucoma should be treated as an ocular emergency and often requires laser treatment in hospital. Occasionally, this type of glaucoma can be treated prophylactically (as a preventative measure) if the eyes at risk are identified.

How is Glaucoma Treated?

The vast majority of patients with glaucoma can be treated medically with eye drops. The treatment is to reduce the pressure within the eye and halt the progression of the optic nerve damage. Although glaucoma cannot be cured, treatment can usually control the disease. If medical treatment fails to control the eye pressure, occasionally laser treatment can be performed, although this is usually only a temporary measure. Glaucoma surgery can be performed in those patients who are not controlled on medical therapy.

Glaucoma Surgery

The most frequent operation for glaucoma is called a trabeculectomy. The aim of this operation is to create a passage for aqueous to drain from the eye into a space beneath the conjunctiva (known as the bleb). It is generally a successful operation but complications may occur, such as excessive drainage causing the pressure to become too low or infection which may be sight-threatening. Excessive scarring beneath the conjunctiva may also cause the operation to fail. Drugs are used frequently nowadays during the operation to prevent scarring (anti-scarring agents).

In very advanced cases or in patients who have certain types of glaucoma, a glaucoma tube can be inserted into the eye to drain away the fluid. This is a major operation with some risk of complications but can offer a useful way of lowering the eye pressure and preventing blindness.

Glaucoma in Children

Discovering your child has glaucoma is a worrying and frightening experience but you can be reassured that everyone working in the ophthalmic department will work as hard as possible to achieve the best possible future for your child's vision. This leaflet will attempt to explain the condition to you, the different treatment options and the overall prognosis for children diagnosed with this condition.

Childhood glaucoma is a potentially serious disease but it is very uncommon. In the United Kingdom, only 1 in every 20,000 children will be born with the condition, which is why you have been referred to Moorfields Eye Hospital, or Great Ormond Street Hospital, which are centres, which deal with this condition on a regular basis. Your local eye clinic may not be able to deal with this, as the treatment is specialised and so you and your family may need to visit London on many occasions, to get the best possible care. A very close working relationship will develop between your child, the family and the medical professionals involved and families usually see the same clinicians who follow the child up long term.

Glaucoma in children can be 'primary', meaning that it occurs out of the blue, with no underlying reason for it. This is termed 'Primary Congenital Glaucoma', or 'PCG'. Sometimes this condition can be inherited, if both parents carry a particular gene. Usually, this occurs if there is some blood relationship between the parents. PCG is the most common cause of glaucoma in children. Glaucoma usually affects both eyes but can affect only one eye in certain cases. Glaucoma also tends to occur slightly more commonly in boys than in girls.

Alternatively, glaucoma can occur as a result of other eye conditions, or be part of another disease. These types of glaucoma are called 'Secondary Glaucomas'. A wide variety of secondary glaucomas occur, the most common occurring after surgery for congenital cataracts. Other types of secondary glaucoma can occur, due to the Sturge-Weber Syndrome, Uveitis (eye inflammation), Aniridia (congenital absence of the iris) and Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome (otherwise known as 'anterior segment dysgenesis'). Glaucoma can occur as part of many other diseases and your eye doctor will be able to explain these to you.

What is Glaucoma?

Glaucoma is essentially a disease that damages the optic nerve, which is the part of the eye that sends electrical impulses from the eye to the visual cortex (the part of the brain that deals with vision). In children, the cause of the optic nerve damage is always high pressure in the eye, which 'presses' on the nerve, causing damage. Optic nerve damage initially damages the peripheral vision but left untreated, can also affect the central vision. Eyesight that is damaged from glaucoma cannot be restored, so the aim of treatment is to prevent further damage to the optic nerve.

Why does the eye pressure increase in children?

In primary congenital glaucoma (PCG), the parts of the eye, which normally drain the aqueous fluid out of the eye, do not develop normally. The fluid builds up in the eye and therefore increases the pressure.

How does the eye pressure affect a child's eye?

The increased eye pressure in a child with glaucoma causes the eye to become larger (buphthalmos). Sometimes people comment that the child has 'big, beautiful eyes' but this can affect the focusing of the eye and cause the child to develop large degrees of myopia (short-sightedness). The high pressure can also cause the cornea (the clear window at the front of the eye) to become 'cloudy' or 'misty', which will also affect the child's ability to see properly. Other common symptoms that might be apparent, are watery eyes (epiphora) and the child may be very sensitive to bright lights (photophobia). Other symptoms may include 'eye rubbing', squint (the eyes do not look aligned) and infants may be reluctant to feed. The treatment for glaucoma aims to lower the eye pressure, thereby clearing the cornea, reducing the symptoms and preventing further damage to the optic nerve.

|

Child with right-sided primary congenital glaucoma. Note the increased size of the right eye compared with left. |

|

Right-sided cloudy cornea, due to elevated eye pressure. |

How can congenital glaucoma be treated?

Almost all children with congenital glaucoma require surgery. In many cases, one operation may be sufficient but often, a series of operations may be required over a period of time, to control the disease. The most appropriate treatment for the child will be discussed by the surgeon and can vary according to the type of glaucoma and other features of the glaucoma, which the ophthalmologist will discuss.

Usually, when surgery is planned, children will be admitted to the hospital for a EUA (examination under anaesthetic). This is to properly assess the condition, which may not be possible in the outpatient clinic. At the EUA, a full eye examination is performed, including a measure of the eye pressure (IOP), an assessment of the degree of optic nerve damage and a measure of the degree of refractive error (for example, myopia). Whilst the child is under anaesthetic, the doctor will then decide which is the most appropriate operation to perform. This will usually be carried out straight away, under the same anaesthetic. The possible treatment options will have been discussed with you prior to the anaesthetic. If everything is stable, no further treatment will be necessary and the child will be woken up, after having a full examination.

What are the more common procedures for congenital glaucoma?

Goniotomy: The goniotomy procedure is usually the initial surgical procedure for PCG. It has been practiced since 1942, so it has a long and successful history. Moorfields Eye Hospital was the first hospital in the UK to carry out this procedure in 1947. The procedure involves making a small incision into the drainage channels, which have not developed normally, to allow the aqueous fluid to start to drain out again. It is a relatively short operation, with few complications. Occasionally, there can be some blood noticed in the front part of the eye after the surgery, which reabsorbs naturally. A stitch is placed in the cornea at the end of the surgery to close the incision but this usually dissolves by itself, so does not need to be removed. Drops will be required for about 2 months after the surgery and usually a further EUA is planned about 6 weeks after the surgery. If the eye pressure is still not adequate at this stage, the procedure is usually repeated, to open more of the drainage channels.

For a goniotomy to be successful, the surgeon has to be able to see the drainage channels clearly. This is sometimes difficult if the cornea is cloudy. In some cases, the surgeon can strip away the outer layer of cells from the cornea, to improve the outcome of the surgery. However, as a result of this, the eye can be uncomfortable for a day or two, while the cells regenerate. It will feel like having an abrasion on the front of the eye but this recovers quickly.

|

A goniotomy procedure involves making an incision in the drainage channels to allow the aqueous fluid to exit the eye. |

Trabeculotomy

Trabeculotomy: This procedure also has a long history behind it, being invented in 1960 by a surgeon at Moorfields Eye Hospital. It is a similar procedure to goniotomy, in that it attempts to open the drainage channels but by approaching them from the outer part of the eye. This procedure is usually recommended when it is difficult to carry out a goniotomy because of more severe clouding of the cornea, even when the outer layer of cells has been stripped away. Again, drops will be necessary for a few weeks after the surgery and another EUA planned after about 6 weeks, to assess the response of the surgery.

Trabeculectomy: Although this procedure is very common in adults with glaucoma, it is not frequently used in children, due to the higher risk of complications and the much more intensive follow up that a child will require. It involves making a 'trap door' in the eye, through which the excess fluid can drain out. It requires very frequent drops afterwards and several EUA's to ensure that the 'trap door' does not heal over.

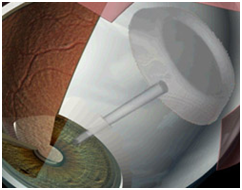

Glaucoma Drainage Device (Glaucoma Shunt)

Glaucoma Drainage Device (Glaucoma Shunt): This procedure is usually carried out if the initial goniotomy, or trabeculotomy has deemed to have failed. With modern surgical techniques, it can have very successful results but is a much more invasive procedure, with more risk of complications than either goniotomy or trabeculotomy. Essentially, a small plastic tube is inserted into the eye, which drains the excess fluid away and therefore lowers the eye pressure. The tube stays in the eye forever and can still function as the child grows up. The most common types of tube implant are the Baerveldt tube and the Ahmed tube.

The main complication to avoid in glaucoma tube surgery is hypotony, which means a dangerously low eye pressure. The Ahmed tube has a special valve built into the tube, which regulates the eye pressure, to avoid the pressure falling too low. The Baerveldt tube does not possess a valve, so the surgeon has to use 2 special stitches to avoid hypotony. The first stitch blocks the tube completely but dissolves naturally after 4 to 6 weeks. Eye drops may still need to be used during this time. The second stitch runs down the middle of the tube, partially obstructing it. In about half the cases, this can be left alone but some children need to have this stitch removed, to gain a lower eye pressure. This involves a small operation but is usually carried out during one of the regular EUA's.

Although the Baerveldt tube takes longer to start working and may need a short second procedure (to remove the stitch), it is usually preferred because it provides a lower eye pressure in most cases and probably works for a longer period of time than the Ahmed tube. There are circumstances however, when it may be more appropriate to use an Ahmed tube and these will be discussed before the surgery.

|

A glaucoma drainage device diverts the aqueous fluid from the front part of the eye, via a plastic tube to a reservoir (plate) around the back part of the eye |

|

The Baerveldt tube implant |

|

The Ahmed tube implant |

Cyclodiode Laser Treatment ('Diode')

Laser treatment can be used to lower the eye pressure, either as an initial procedure, or following other surgeries, if the eye pressure is still not adequately controlled. Diode laser is considered to be a temporary treatment for elevated eye pressure, as the cells that have been treated by the laser, eventually regenerate and the eye pressure increases again. However, the advantage of laser treatment is that it does not involve conventional surgery and is very rapid to carry out. As a result, it has a much lower frequency of complications and can also be repeated if necessary. There is however, a maximum number of laser procedures that can be performed, before other complications can occur. Usually, 2 or 3 procedures are recommended as a maximum.

All surgical procedures nowadays can be carried out as 'day case' surgery, so an overnight stay in hospital is not usually required.

What happens after surgery?

Controlling the eye pressure is usually the first part of the treatment for congenital glaucoma. Following successful surgery, the long-term management includes treating any degree of short-sightedness (with spectacles, if necessary) and treating amblyopia (lazy eye). This might include putting a patch over the better eye for a certain period each day, to 'force' the weaker eye to start working. Children with poor vision are reluctant to keep the patch on but it is the only effective treatment for amblyopia and the child must be encouraged to keep the patch on. If a child still has a 'lazy eye' after the age of 7 years, there is no treatment that is then able to improve this.

The glaucoma will still require frequent follow up examinations, as it is a lifelong condition and may also need to use some drops, even in addition to the surgery that has been performed.

What will my child's vision be like?

Although glaucoma in children is a serious condition, many children can have normal vision. For primary congenital glaucoma, about one third of children will have vision that will enable them to drive a car. About one third of children will be 'partially sighted', to some degree but will be able to attend mainstream school and be able to have regular employment. Unfortunately, about one third of children will have vision that is classified as being 'severely visually impaired'. However, many children in this group, with appropriate support are still able to attend mainstream school and have suitable employment.

Treating children with glaucoma requires a multidisciplinary team. As well as having a close relationship with the surgeon, you will also meet nurses, orthoptics (professionals who deal with vision development), optometrists and family support. The family support team act as a bridge between the hospital services and the outside world, especially in terms of liaising with educational services, to ensure that the child has adequate support at school, usually via the statementing process, which identifies individual needs for a child's education. As in many cases, families have to travel large distances on a regular basis, there may also be assistance in travelling costs and help with overnight accommodation, if surgery is required, so children are not travelling great distances on the day of surgery itself.